MATTHEW ATTARD

Why would anyone – you or artist Matthew Attard – choose not to see a social media feed or a webpage? The internet was created to connect far away worlds and lives while expanding our visual experience and placing pseudo-knowledge at our fingertips. However, we have learned that when we scroll or swipe, we participate in our own compartmentalization, producing data that will be used to feed the algorithms devised by international corporations and other powerful private and public entities that control the imageries we see on the internet. IP addresses, but also social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat and Tik Tok are only the latest and most effective tools of global surveillance and Marketing 2.0, aimed at the prediction and monetization of social behavior and the standardization of perception across different cultures and backgrounds.

An artist and Millennial might conclude that there is no cultural compass or alternative left to beat this commodification of imagery and the colonization of attention by increasingly techno-economic processes[1]. Yet Matthew Attard, while acknowledging the impossibility of subtracting oneself from the daily intake of imposed images, does not withdraw from the internet as many artists of his generation have done. While many turn back the clock as a form of resistance, choosing to appropriate traditional techniques of painting and carving to relate personal mythologies, Attard draws with a digital eye tracker, online and offline.

The eye tracker is one of many technologies used today for biometric surveillance and it is specifically made to capitalize on our visual attention. The study of eye movement began in the late XIX century after the invention of photography in 1839, yet the digital eye tracker based on human-computer interaction is an invention of the 1980s. Since the 2010s it has become a headset, resembling a bulky pair of glasses. The integrated camera on the frame records the shifting locations of the gaze point – thus while it cannot direct you to a particular image or object, it does know what you saw, and makes it visible. Not too many individuals are familiar with it or use it for personal entertainment, yet the eye tracker is still quite widespread in gaming, big data and social media.

Matthew Attard applies his interest in the eye tracker to rethink drawing in the XXI century as a somehow impure hybridization of human and machine which challenges the notions of authorship and style in art. These ideas have been the bastions of art history for centuries, yet atomization and digitalization have opened up opportunities in every field of human action, and culture is no exception. Besides inspiring new processes, they are also questioning the borders between digital content, a startling visual object, and art itself.

Both an extra pair of eyes and “a seismographer”, in Attard’s words, the eye tracker is capable of collecting even the slightest move and processing it with its own visual language – a syncopated, impersonal line suspended between figuration and abstraction[2]. Unsurprisingly, Attard’s first use of the eye tracker in 2017 in the Eye Drawing series, after a few years spent studying the technology, fell into the categories of social experiment and performance. He would gather a diverse group of people for a traditional “life class”. Then, he asked them to draw using their eyes instead of their hand, an activity that required a reset of their idea of art making, which to date is based on human control, acquired cognitive processes, and cultural heritage.

Drawing as a collective experience wearing the eye tracker also educated Attard on how people of different ages and backgrounds understand human-techno relations. During the pandemic, however, Attard had to change course of action. His experiments were halted by social distancing restrictions, and so he opted for a more private investigation of life’s new emphasis on screens and social media rather than real life situations. As he repurposed the eye tracker to assess the emotional consequences of a more “mundane” dependency on virtuality, he sensed growing eye fatigue and disengagement, as well as a narrowing attention span in response to the enforced processes and repetition which command the internet.

Attard’s response was particularly strong to Tik Tok, which he targeted to explore the way one of the newest and most successful social platforms unpacks and abuses the mechanisms of vision. In the technocratic digital society, Tik Tok holds a special place because it attracts an array of subcultures from all over the world, it is fast growing and yet the algorithm openly rules the platform. It profiles the new user by offering content in real time, unveiling its plan to use the user, something that does not seem to bother most TikTokers.

Ultimately, Tik Tok is a choice. There is no urgency or need about Tik Tok; the platform is a time filling occupation, offering the distraction of a performance-driven society and rescue from horror vacui. Its success in doing so has a scientific explanation. Because a coherent picture of what is seen is a synthesis of the constantly shifting information caught by the eyes, Tik Tok’s content is programmed to solicit visual attention incessantly through color and sound in order to exploit the mix of memory and perception.

Here’s how I did not see what you wanted me to see (2022) is the first interactive artwork by Attard. Its many layers and trails produce a journey devised by the artist to bring “customer awareness” to users whose traces on social media are sold to governments and international corporations to predict behavior and sell products. To do so, Attard conjured an “artistic sabotage” of Tik Tok by way of misusing the eye tracker to regain agency and user power. Attard’s artwork, first and foremost, could be considered an attempt to steal a technology from the market.

The title, Here’s how I did not see what you wanted me to see (2022), is an homage to artist Hito Steyerl’s militant research on visibility and surveillance; however, it can also be read as a declaration of “intentions” to resist the monetization of the gaze by Tik Tok. Viewers can engage at different levels in the artwork, and spend as much time as they want, because Attard is sharing the driver’s seat with them. It all starts on the first page, where a black background shows the title of the piece in a white font followed by a red start button. Upon clicking on it, the viewers can access a second page with similar aesthetics stating:

TikTok users spend an

average of 1.5 hours per day

on the platform.

I spent 1,5 hours scrolling

through the platform while

trying to not look at the

content.

Start scrolling or swiping to

See how I did not see it.

The note is in verse, and a few words are underlined in red. With The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (1967), artist Bruce Nauman entrusted a powerful statement about the role of the artist in our society to a blue, white and red neon sign, a medium of mass culture meant to embody the message for everyone, outside of art’s traditional marble and canvas. Behind statistics, instructions and an ironic attitude towards the medium and the message, Attard presents a similar yet updated version of that subject, broadened by the invention and commodification of the internet, the greatest circulator of images of all time.

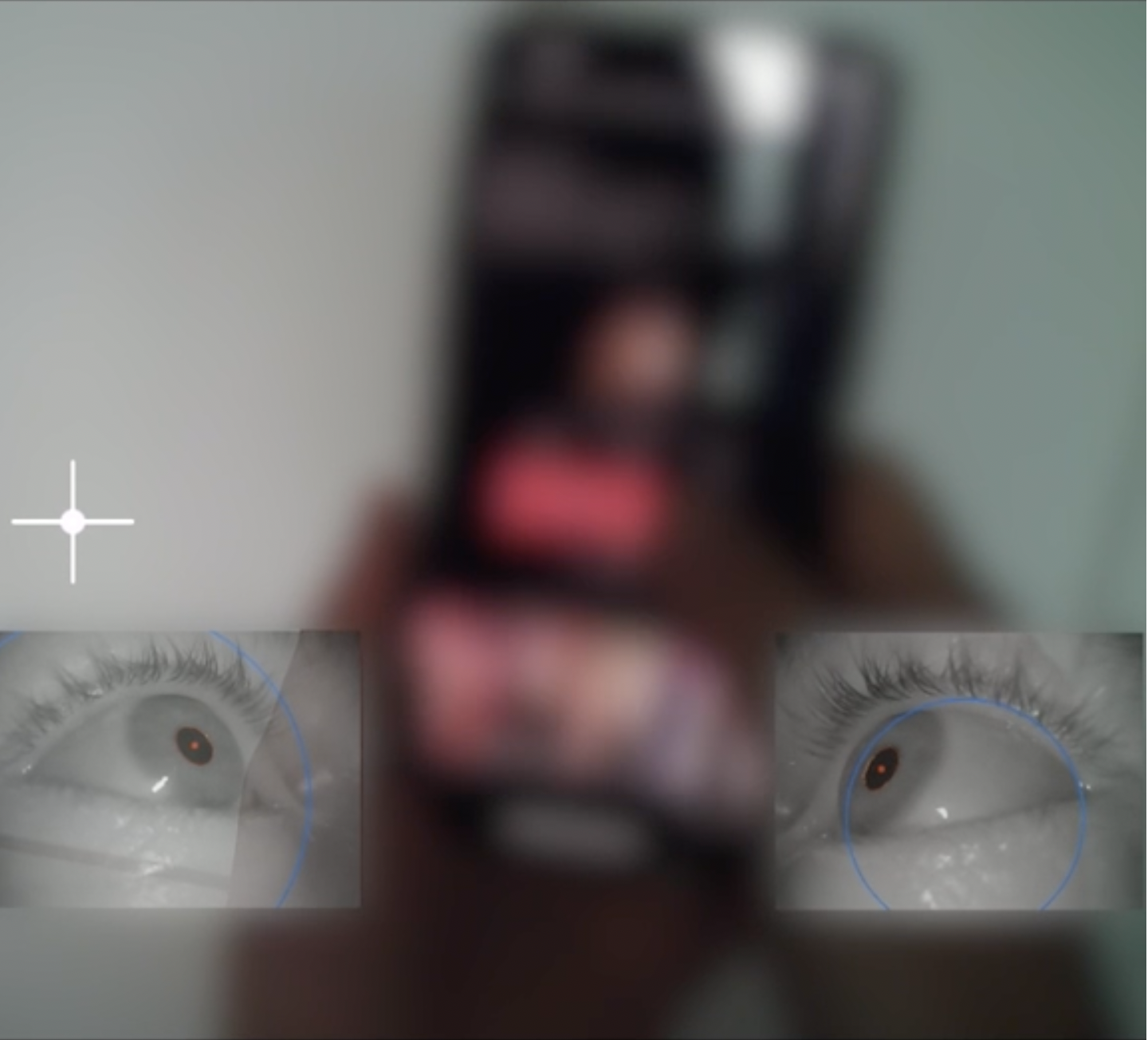

This second page is also activated by the Tik Tok voice, a linguistic appropriation which is only recognizable by actual Tik Tok users. The gap – generational, technological – among different users grows as they start scrolling down and are immediately redirected to a third page. Here, the artist’s Tik Tok feed runs fast at the centre of the page, superimposed by the line of the eye tracker and framed by Attard’s eyes filmed in black and white and inscribed into two blue circles. The images of the feed have been darkened and are barely recognizable, thus the focus of attention is the report offered by the camera and the drawing capabilities of the eye tracker illustrating Attard’s failing attempt at “not seeing”, his eyes mirroring those of the viewers.

When viewers eventually stop scrolling, they are sent to a still page, the fourth page, topped by what looks like a logo – a circle with an eye tracker drawing inside – followed by information regarding the time (in minutes) and space (in an iPhone 12 Pro’s height) of their virtual journey. Attard shares the information he gathered on the viewers’ activity, mimicking the corporate style of big data, but incongruously uses an unconventional parameter to measure space, revealing a subtle critique.

Once again, Attard offers the choice to scroll or click on a red button which states “I am bored” – something hardly admitted or noticed by social media users when hypnotized by uninteresting yet stimulating contents. The scrolling choice gets the viewers back to the eye tracking experience of watching the artist’s activity on a Tik Tok feed, while the “I am bored” button opens up a fifth page where a viewer’s statistics are taken one step further and compared to others. A drawing framed by a white line, instead, reveals that the movement of the viewers’ finger on the screen or touchpad was also monitored. In exchange for the free behavioral data set, the artist generously shares the drawing in a format that can be printed by clicking on another red button. Alternatively, one can start everything over again, launching an internet loop.

On Blitz Valletta’s website, Attard invites the users to experience a deconstructed exhibition – to see, read, and follow. Each possibility, identified by a button, corresponds to an alternative journey into the artist’s process – even the backstage – as if Attard wanted to leave nothing untold in a “I post therefore I am” world, to update René Descartes’s principle. While the seeing and reading experiences immediately launch on the opening day, the “follow” – a curated feed of eye contents and challenges found by the artist during his Tik Tok safaris – grows over time. Also, another button flashes up during the exhibition, under the name “big data”, referencing the material collected by the artist. On this page, users can read information on all the other users of the artwork and print any drawing they want, out of Attard’s decision to not monetize his artwork’s collective output. Ironically, at the top of this closing page, the artwork’s title displays a fundamental edit and reads “Here’s how I saw what you did not want me to see”.

In Here’s how I did not see what you wanted me to see (2022), artist Matthew Attard fails to resist looking at the addictive content conceived by Tik Tok to turn him into a product to sell, yet at the same time he exposes the invisible power game played at the expense of the user and creates a portal to a new market with art products of tech-culture available to all, and thus of no economic value. According to Bruce Nauman’s lesson, he could be engaging in revealing the “mystic truth” like a true artist should.

[1] A detailed history of the internet and its origins is told by Shoshana Zuboff in The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, Public Affairs, Hachette Group, New York, 2019.

[2] More information on the eye tracker and the way it functions can be found in Jonathan Crary, Notes on Eye Tracking, Harvard Design Magazine, No. 46, Fall-Winter 2018.

CREDITS

Joey Borg, web developer

Sara Dolfi Agostini, curator

Alexandra Pace, web and digital designer

Valentina Tanni, digital arts specialist and mentor of the Blitz Digital Residency

International visiting professors:

Kenneth Goldsmith, artist and founder of the online archive UbuWeb

Ben Grosser, artist

Domenico Quaranta, art critic and curator

PROJECT SUPPORTED BY